Lost And Helpless At a Camp In Chad

“My name is Amani E. and I am a refugee from Darfur currently living in the Cary Yary Refugee camp in eastern Chad. I was born in Amboro village, in north Darfur, and I used to work as an elementary school teacher. I loved my job. Now I am a widow, and I raise two beautiful daughters who have lost their dad.

On January 27th, 2004 , our lives changed forever. On that night, a plane dropped bombs on our village, hitting people’s houses and public buildings such as schools and hospitals. Soon after, ground troops belonging to the Sudanese government and the Janjaweed (government-sponsored militia) came by foot and started shooting everyone and everything that moved – even a plastic bag blown by the wind. They wanted to ensure that the whole village was destroyed. People started running in different directions, but were hunted down and shot to death. However I try to describe this scene, I certainly will not do justice to the brutality of the attack. Hundreds of people were killed. I lost two nephews, two other immediate family members, and 10 extended family members.

Some of us managed to run to the mountains for safety. Unfortunately, the soldiers followed us and set fire to the mountains. We continued running. Eventually we decided to flee all the way to the neighboring country Chad, where we would be safe. We had to walk for 7 days before we reached a city on the border called Bahai, where we settled. In the confusion, families were separated and many people went missing. We later learned that some people fled to different refugee camps, but most of them were killed.

Our new home was a dry desert with very few trees. It was windy and dusty. Many people felt sick and there was no medicine. We had to improvise in order to survive. We walked took daily walks to a nearby forest, where we gathered wood to make food and straws to use as clothes and sheets. It was much later when the humanitarian organization International Rescue Committee came to us offering basic aid such as food and health assistance. Even then we felt lost and helpless. We had lost everything.

Our new home was a dry desert with very few trees. It was windy and dusty. Many people felt sick and there was no medicine. We had to improvise in order to survive. We walked took daily walks to a nearby forest, where we gathered wood to make food and straws to use as clothes and sheets. It was much later when the humanitarian organization International Rescue Committee came to us offering basic aid such as food and health assistance. Even then we felt lost and helpless. We had lost everything.

Before the genocide began, life was beautiful and stable. We had limited resources and services, but we were happy. People in my village were productive. They were farmers, owners of livestock, civil servants, teachers, health professionals, and traders. Women were part of every occupation as active members of our community, working hand in hand with men and actively involved in all aspect of daily life. They were productive while still providing for their families. And we were lucky to have extended families that would help each other. Today that has become a distant dream.

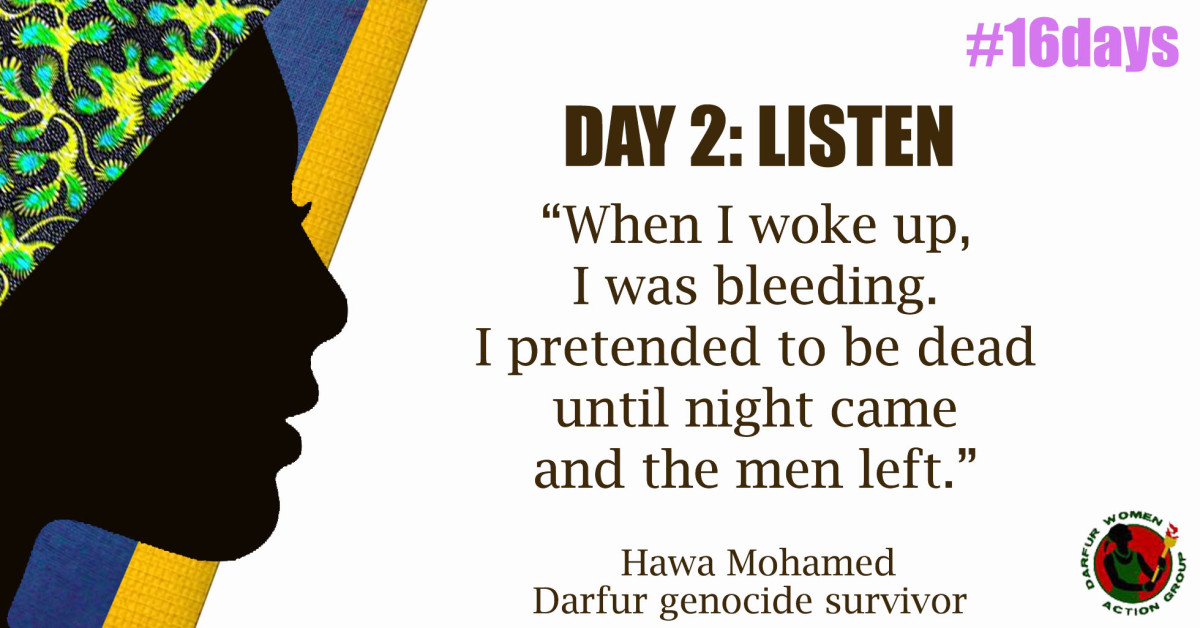

Most of our people have now been uprooted from their place of origin, humiliated and forced to become homeless. We continue to count our losses, which include our social fabric, our culture and unique values. Life has become very different. We have been oppressed, subjected to economic and social exploitation, psychological stress and trauma. Darfuri women have suffered unimaginably. Not only have we mourned the loss of husbands, children and loved ones, but also we have lost our power. We went from being productive to being helpless.

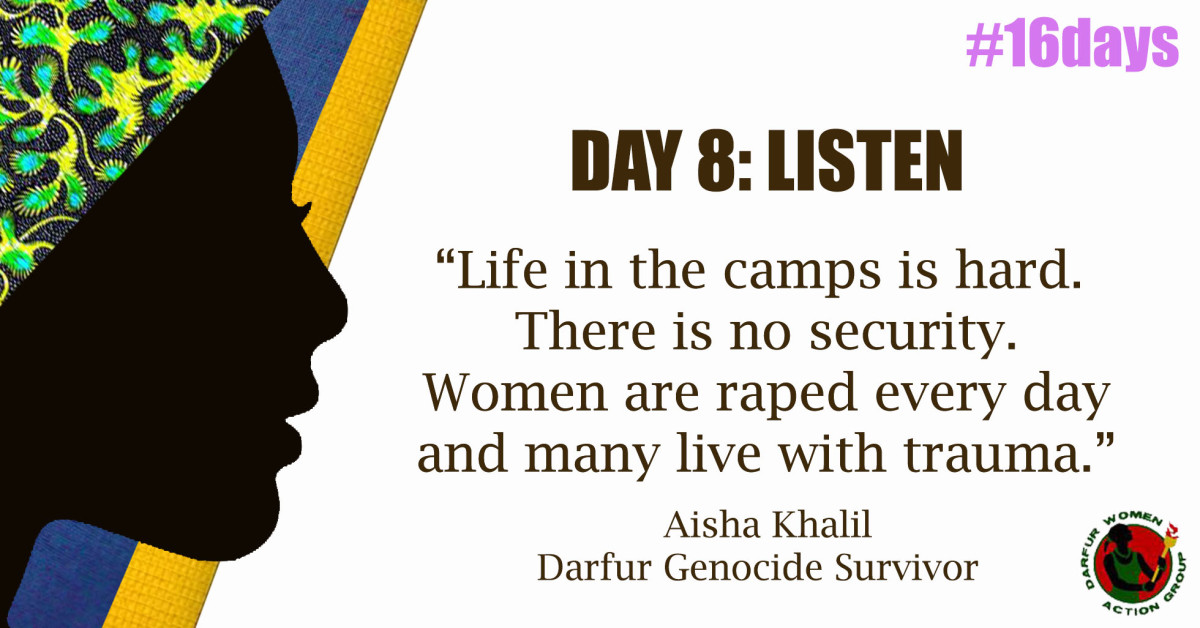

The overwhelming majority of the population in camps today are women and children. It is no way to live. We have no home, no property, no privacy and no protection. With many of the men gone to fight, we bear the primary responsibility of providing to our families. But there are limited options to make an income – and they are all risky. We can work in harsh labor, such as manual brick making or construction. Another alternative is to walk daily to the forest to collect firewood or straws to sell in a local market, which puts us at risk of being raped. It is humiliating, but many women have to accept this risk because it is the only mean of survival for their children and families.

Having watched the difficult situation of women for many years, I refused to stay helpless. I started a support group to empower women who live in the camps, and to encourage them to speak up about the dire conditions that they face on a daily basis. I wanted to teach these women how they can (and should) participate in the decision making of their communities, including the peace-building effort. We have been completely absent from all the regional and international peace forums, which is very disappoint to me. We have been sidelined and deprived from our rights to participate in whatever is happening regarding Darfur.

Since the group was created, we have reached out to regional and international actors who are working to bring peace to Darfur, including the British Ambassador, and the United States Special Envoy for Sudan and South Sudan. We explained to them that Darfuri women are the most affected by the genocide, and yet we are left behind in all the peace efforts. We told them that women are the backbone of our society in all aspects, including economic, political, and social, because of the role that we used to have in our communities, and the new roles that have emerged during the crisis.

Recently we heard some talk about an improved situation in Darfur and the return of many people to their villages. To me that is a big lie. As someone who has lived through all of the crisis and who is still living, the reality is that the conditions that forced millions of people to flee has not improved. In fact, it probably has deteriorated. Sadly, there is still no security in Darfur or any sign of lasting peace. At to make matters even worse, the humanitarian assistance that we use to receive in camps has been dramatically reduced, making our survival nearly impossible.

I would like to appeal to everyone to stand with the women of Darfur, and to help them fight for their rights and to restore their dignity.

My hope for the future is to obtain a master’s degree to continue my work educating women. I also want to educate the next generation of Darfuris, in order for them to have a better future. I hope want to raise my daughters to be strong, and to stand up for their rights and the rights of others. Thank you Darfur Women Action Group for giving me this opportunity to contribute. I hope we will continue to work together to empower women, so that we can all speak in one voice and fight for our rights.”

—

TAKE ACTION. Please join us in taking at least one action that will help end violence against women in Darfur:

- Raise awareness by sharing our campaign content on social media, using the hashtags #16Days and #StopRapeInDarfurNow.

- Tag United Nations on social media and demand accountability for the 2014 mass rape in Darfur. Share it with 10 people in your network. Use @UN on Twitter and @UnitedNations on Facebook.

- Donate to DWAG to support a rehabilitation center for women survivors of sexual violence in Darfur.

- Join our Rapid Response Network, a group of community members who are on standby to help us with campaigns and petitions.

- Send a solidarity message that we can share with our supporters and the women in Darfur: communication@darfurwomenaction.org.

Our new home was a dry desert with very few trees. It was windy and dusty. Many people felt sick and there was no medicine. We had to improvise in order to survive. We walked took daily walks to a nearby forest, where we gathered wood to make food and straws to use as clothes and sheets. It was much later when the humanitarian organization International Rescue Committee came to us offering basic aid such as food and health assistance. Even then we felt lost and helpless. We had lost everything.

Our new home was a dry desert with very few trees. It was windy and dusty. Many people felt sick and there was no medicine. We had to improvise in order to survive. We walked took daily walks to a nearby forest, where we gathered wood to make food and straws to use as clothes and sheets. It was much later when the humanitarian organization International Rescue Committee came to us offering basic aid such as food and health assistance. Even then we felt lost and helpless. We had lost everything. “I was born in Kurdufan, an area in Western Sudan. My family is from Darfur and still live there, so I consider myself to be a Darfuri as well. As a child, I used to enjoy watching movies on television, particularly the ones that had female characters that were journalists. They seemed so empowered and independent – everything that I wanted to become someday. As a teenager, I began imitating those characters by writing for school magazines and newspapers. I eventually went to college to study journalism. In 2001, I graduated and started working for a local newspaper in the capital of Sudan.

“I was born in Kurdufan, an area in Western Sudan. My family is from Darfur and still live there, so I consider myself to be a Darfuri as well. As a child, I used to enjoy watching movies on television, particularly the ones that had female characters that were journalists. They seemed so empowered and independent – everything that I wanted to become someday. As a teenager, I began imitating those characters by writing for school magazines and newspapers. I eventually went to college to study journalism. In 2001, I graduated and started working for a local newspaper in the capital of Sudan. also took me to court and unjustly charged me with the crime of “publishing false news”. A Sudanese court tried my case and ruled that I was guilty. A judge sentenced me to one month in jail, unless I paid a fine of 2,000 Sudanese pounds (US$ 300). Five other journalists were accused of the same crime at the time, but were released. Another female journalist was sentenced along with me, but she filed an appeal and was also released. I believe that I was particularly targeted because I have roots in Darfur – and the government does not look kindly on Darfuris.

also took me to court and unjustly charged me with the crime of “publishing false news”. A Sudanese court tried my case and ruled that I was guilty. A judge sentenced me to one month in jail, unless I paid a fine of 2,000 Sudanese pounds (US$ 300). Five other journalists were accused of the same crime at the time, but were released. Another female journalist was sentenced along with me, but she filed an appeal and was also released. I believe that I was particularly targeted because I have roots in Darfur – and the government does not look kindly on Darfuris.

We kept running for most of the night. A few hours before dawn, someone in our group said that we should stop, find a place away from the road and get some sleep. I was very thirsty, but luckily a woman who looked just like my mother had a gallon of water that she had been carrying on her back. She gave each one of us a sip of water – but just a little, because there was a long road ahead of us and the water had to last. People started counting their family members, and I found that my youngest sister and brother were missing. I cried, and decided that I could not go ahead without them. I wanted to go back to the village to find them. But others in the group convinced me that there was no one left in the village, and that when we reached the city I would be reunited with my family.

We kept running for most of the night. A few hours before dawn, someone in our group said that we should stop, find a place away from the road and get some sleep. I was very thirsty, but luckily a woman who looked just like my mother had a gallon of water that she had been carrying on her back. She gave each one of us a sip of water – but just a little, because there was a long road ahead of us and the water had to last. People started counting their family members, and I found that my youngest sister and brother were missing. I cried, and decided that I could not go ahead without them. I wanted to go back to the village to find them. But others in the group convinced me that there was no one left in the village, and that when we reached the city I would be reunited with my family.

#GivingTuesday is a global day of giving that brings diverse organizations and communities around the world together to give back. Our team is pleased to invite you to take this opportunity to engage in something meaningful for you and others.

#GivingTuesday is a global day of giving that brings diverse organizations and communities around the world together to give back. Our team is pleased to invite you to take this opportunity to engage in something meaningful for you and others.

“I lived in a beautiful village in Darfur surrounded by tall acacia trees. Towards the west there was a green valley named Azum that provided us with mango, guavas, oranges, and beautiful gardens for six months during the rainy season. Toward the east there were sugarcane farms. I considered everyone in my village to be rich. Through hard work they cultivated all types of grains, vegetables and fruits. They also raised goats, sheep and cows. Most people had what they needed to survive and only went to the market to buy clothes, soap and sugar. Everyone was very friendly and supportive. If you needed help building a house, the community would come together and finish the house in one day. Life was beautiful and I was very happy.

“I lived in a beautiful village in Darfur surrounded by tall acacia trees. Towards the west there was a green valley named Azum that provided us with mango, guavas, oranges, and beautiful gardens for six months during the rainy season. Toward the east there were sugarcane farms. I considered everyone in my village to be rich. Through hard work they cultivated all types of grains, vegetables and fruits. They also raised goats, sheep and cows. Most people had what they needed to survive and only went to the market to buy clothes, soap and sugar. Everyone was very friendly and supportive. If you needed help building a house, the community would come together and finish the house in one day. Life was beautiful and I was very happy. . And after six months, I was finally reunited with my husband. Since the attack to our village, he had been missing. I learned that he had been seriously wounded and was in a remote village in Darfur. I notified the International Rescue Committee and, thankfully, they found him and brought him to Chad. When he arrived, I could barely recognize him. Due to his injuries, he became permanently physically disabled.

. And after six months, I was finally reunited with my husband. Since the attack to our village, he had been missing. I learned that he had been seriously wounded and was in a remote village in Darfur. I notified the International Rescue Committee and, thankfully, they found him and brought him to Chad. When he arrived, I could barely recognize him. Due to his injuries, he became permanently physically disabled.

THIS IS IMPORTANT.

THIS IS IMPORTANT.